The Older Patient

Pain Assessment

Pain is often unrecognised and undertreated in older patients. They may have pre-existing painful conditions such as arthritis as well as pain from their admission diagnosis.

Pain management in the older patient is complicated by other comorbidities – particularly cardiovascular and renal disease – and their attendant polypharmacy, where their other medications may increase risk with NSAIDs or sedation with opioids. Changes in physiology and drug pharmacokinetics also contribute to the need for a more considered approach to prescribing in the older adult, and careful monitoring.

Pain assessment

Older patients often use different language to describe their pain - “it’s sore, it’s uncomfortable, it aches” – so if a patient denies pain using the usual verbal rating scale it is important to ask more questions to confirm no discomfort.

Pain assessment should include “pain at rest” to guide prescribing of regular analgesia, and “pain on movement” (e.g. when moving from bed to chair, or taking a deep breath) to guide prescribing of PRN analgesia.

Patients with dementia or acute delirium who are unable to answer direct questions should have pain assessment using the Abbey Pain Scale. Family and carers should be included in the assessment process as they may identify subtle changes in behaviour which may reflect pain.

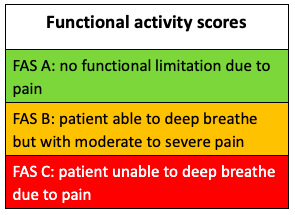

The Functional Activity Scale (FAS) is useful to assess recovery and also guide analgesic prescribing. For example, a patient with rib fractures would score:

· A if able to deep breath and cough without limitation – no analgesic changes needed

· B if deep breathing and coughing possible but limited by pain – encourage more use of PRN analgesia or increase doses

· C if in too much pain to do either – refer to the anaesthetic team for consideration of a local anaesthetic block

Pain Management

Studies have shown that ward staff tend to underestimate pain needs, under-prescribe analgesia and under-medicate. This is often related to concerns over co-morbidities or polypharmacy.

Use a multimodal approach to analgesia using the safest drugs administered via the safest route, then escalating treatment if analgesia is ineffective. For many analgesics a lower initial dose may be required compared to younger adults, with subsequent doses titrated to response. Careful titration is needed to achieve analgesic efficacy without side effects.

Treatment should be regularly evaluated for efficacy and safety.

Analgesia is important to allow mobility and physiotherapy. This will strengthen muscle support of painful joints which will ultimately improve symptoms.

Consider non-pharmacological methods of analgesia: reassurance, change of bed or chair, splinting of fractures, ulcer dressings.

Contact the pain team if needed for more support and advice.

Practical Guidance

- Give regularly qds for background pain and for the opioid sparing effect

- Reduce dose to 500mg qds if weight under 50kg, or if weight above 50kg but evidence of malnourishment

NSAIDs

These are very effective analgesics but are often underprescribed due to concerns over adverse effects. Risks increase with age so avoid if older than 75 years old.

If younger than 75 years old, do not give if the patient:

- is on digoxin, diuretics, beta-blockers, calcium antagonists, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, warfarin, other anticoagulants, or corticosteroids

- has heart failure – do not give if NYHA 3 or 4

- has renal dysfunction – do not give if eGFR under 60

- has a history of GI ulceration

If younger than 75 years old and no contraindications:

- Give regularly – e.g. ibuprofen 400mg tds – and use for the shortest time necessary -e.g. a 3-day course and not given as a TTO

- Give proton pump inhibitors routinely for gastric protection

- Monitor renal function

Opioids

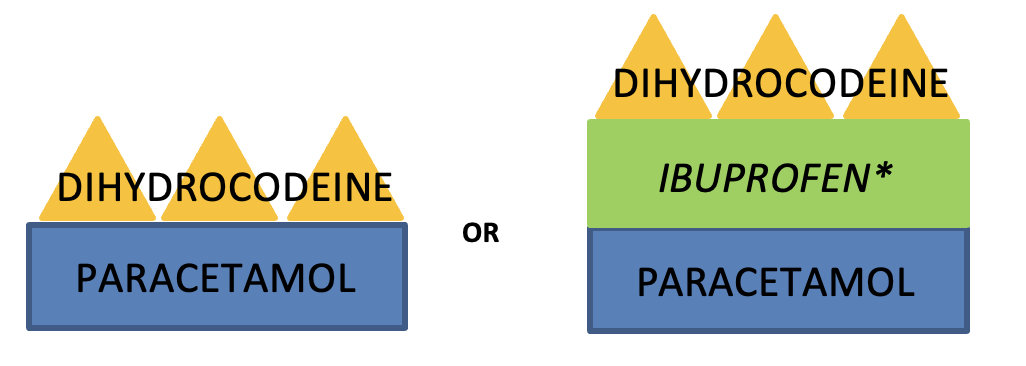

- Initially give a weak opioid PRN e.g. Dihydrocodeine 15-30mg 4hourly (for pain on movement or breakthrough pain which, by definition, is intermittent and short-lasting) and be proactive in its use: give 15 mins before physio, moving to a chair, or turning in bed etc

- Use may be limited by constipation, nausea, drowsiness or delirium, so it is important to avoid giving regular opioids if not needed

- Do not use dihydrocodeine or codeine in patients with eGFR below 30. Instead use small doses of oxycodone (see below)

*only use NSAIDs if no contraindication, and use with caution.

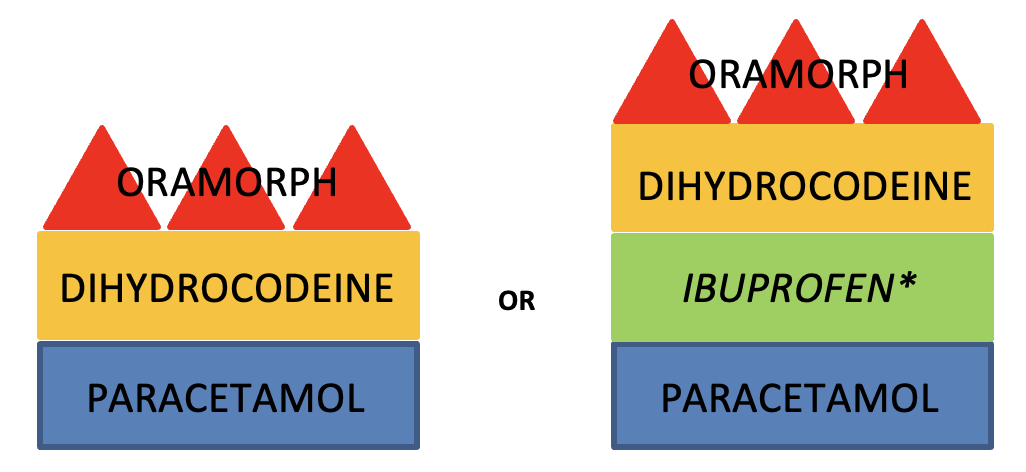

· If pain at rest is not well controlled, consider increasing background analgesia by giving regular dihydrocodeine and adding immediate-release morphine sulphate solution such as Oramorph PRN at a dose of 2.5-5mg 2hourly. This is a recommended initial dose, so if pain on movement is still restricting physio and recovery despite proactive use, the doses can be increased as tolerated.

· If the patient has renal dysfunction – eGFR below 30 – oxycodone should be prescribed in place of morphine. Oxycodone is 1.5 – 2 times stronger than morphine so a smaller initial dose – e.g. 1.25mg 4 hourly PRN – is more appropriate

-

Tramadol causes fewer respiratory and gastrointestinal side effects than other opioids but is associated with delirium, and can often cause nausea, vomiting, sweating, dizziness, tremors and headaches. Rarely it can cause seizures and serotonin syndrome if prescribed with SSRIs. Codeine or dihydrocodeine is generally preferred for the older patient.

-

Strong opioids: start low and go slow. Give short-acting opioids (e.g. immediate-release Morphine or Oxycodone) 15-30 minutes before an expected painful event such as physiotherapy, mobilisation or being turned in bed.

- Ensure that patients are regularly monitored with sedation scores (most sensitive) and respiratory rate to identify opioid toxicity.

- Prescribe PRN naloxone (40microgram boluses) if strong opioids are prescribed.

- Give regular laxatives if opioids are prescribed.

-

Management of constipation MIL: http://ouh.oxnet.nhs.uk/Pharmacy/Mils/MILV8N10.pdf

- Consider Gabapentin (e.g 100mg tds)or pregabalin (e.g.25mg bd) for neuropathic pain.

- Depression may be expressed as pain, so a holistic approach is important.

Delirium and falls risk

Delirium

Opioids are not the only cause of confusion, so ensure that other causes are sought and excluded, eg hypovolaemia, hypoxia, sepsis (including UTI), electrolyte disturbances, hypo- or hyperglycaemia, renal or hepatic dysfunction, CVA. Confusion is common after a general anaesthetic or after a stay in intensive care.

Pain is also a cause of confusion so stopping analgesia may worsen, not improve, the situation.

If other causes have been excluded and opioids may be contributing to confusion, consider reducing the opioid load by stopping the regular opioids. Ensure that PRN opioids are still available for breakthrough pain from mobilisation etc. Consider changing the Morphine to Oxycodone.

Falls

Polypharmacy in older patients has been found to increase the risk of falls. Although analgesics themselves do not appear to increase risk, benzodiazepines and tricyclic antidepressants (e.g. amitriptyline) are associated with a high risk of falling so should be used with care.

Medications that contribute to the risk of falls MIL: http://ouh.oxnet.nhs.uk/Pharmacy/Mils/MILV7N6.PDF

Rationalising long-term analgesia

A hospital admission provides an opportunity to rationalise long-term analgesic medication – opioids, gabapentinoids, amitriptyline, duloxetine – that the patient may have been taking for years or decades, with now unclear benefit, but possibly increased risk. All of these drugs have associated withdrawal syndromes, so any reductions should be first discussed with – and agreed by – the patient, and should be slow, with the plan clearly communicated to the GP on discharge, particularly if the reduction needs to be continued longer term.